What is the 90-year-old tax rule Trump could use to double US taxes on foreigners?

US President Donald Trump isn’t happy about the way some countries are taxing American citizens and companies. He has made clear he’s willing to retaliate, threatening to double taxes for their own citizens and companies.

Can Trump really do that, unilaterally, as president? It turns out he can, under a 90-year-old provision of the US tax code – Section 891.

In an executive memo signed on January 20 outlining his “America First Trade Policy”, Trump instructed US Treasury to:

investigate whether any foreign country subjects United States citizens or corporations to discriminatory or extraterritorial taxes pursuant to Section 891 of Title 26, United States Code.

A sweeping power

Section 891 of the US Internal Revenue Code is short, but it is in sweeping terms.

If the president finds that US citizens or corporations are being subjected to “discriminatory or extraterritorial taxes” under the laws of any foreign country, he “shall so proclaim” this. US income tax rates on the citizens or corporations of that country are then automatically doubled.

The extra tax that could be collected is capped at 80% of the US taxable income of the taxpayer. The president can revoke a proclamation, if the foreign country reverses its “discriminatory or extraterritorial” taxation.

Section 891 is an extraordinary provision – but it has never been applied. As far as I know, no other country has legislated such a rule. Importantly, it would only apply to a person or business subject to income taxation by the US.

Take, for example, a foreign national earning a wage in the US. If this individual’s home country became subject to a proclamation under Section 891, their individual tax rate in the US would be doubled - to as much as 74%.

A foreign company earning taxable profits in the US would face a doubling of the company tax rate from 21% to 42%.

A bit of history

A version of Section 891 has been in the US tax code since 1934, an earlier troubled time of tax disputes and economic depression.

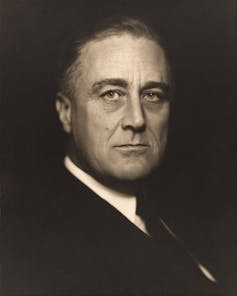

It was signed into law by Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt on May 10 1934, amid a tax dispute between the US and France.

According to US tax historian Joseph Thorndike, the move followed attempts by France to levy additional taxes on US companies operating there, beginning in the mid-1920s.

France had tried to use an 1873 law to tax US companies operating in France on profits earned in the parent company back in the US, and in other subsidiaries around the world, not just the French company profits.

The aim was to counter international profit-shifting, which could be used to reduce the tax payable by US subsidiaries operating in France by claiming deductions or shifting income to other group companies outside France.

The dispute was long-standing and France tried to assess taxes going back decades for some US companies. The potentially massive tax bill (it seems the tax was never actually collected) became a geopolitical issue, and the companies asked the US government to intervene on their behalf.

Thorndike explains that a bilateral tax treaty was negotiated between the US and France to remedy this “double tax” situation. But the French legislature refused to ratify it.

In retaliation, US Congress passed Section 891, and six months later, France ratified its bilateral tax treaty with the US.

Parallels with today

In 1934, there were no digital multinational enterprises like Meta or Google. But that tax dispute nevertheless has parallels with modern concerns about taxing companies internationally.

The French government was trying, with a rather heavy hand, to counter international profit-shifting by large US multinationals.

Section 891 was re-enacted in later US tax codes, up to today, with minor amendments and no attempt to invoke it. It has remained in the background as a potential exercise of US fiscal and market power, supported by both sides of US politics.

Tax professor Itai Grinberg, who worked in the Biden administration on the OECD tax deal, suggested it could be applied to the European Union decision that taxes Apple in Ireland.

What might Trump do?

President Trump has specifically targeted the OECD global tax negotiations with this threat, just a month after Australia has legislated the global minimum tax under “Pillar Two” of the OECD Global Tax Deal.

The OECD deal aims to ensure large multinational enterprises pay a minimum 15% effective tax rate in all the jurisdictions in which they operate, by applying a top-up tax and under-taxed profit tax.

Trump asserted in a memorandum that the OECD Global Tax Deal is “extraterritorial”, instructing the US Secretary of the Treasury and the US Trade Representative to investigate it.

Could Australia be singled out?

Trump’s memorandum also ordered an investigation into “other discriminatory foreign tax practices” that may harm US companies.

This includes whether any foreign countries are not complying with their US tax treaties or have, or are likely to put in place, any tax rules that “disproportionately affect American companies”.

Notably, this could put Australia’s proposed “news bargaining incentive” in the crosshairs.

Under this proposal, digital platforms (many of which are US-owned) would have to pay a new levy, which could be offset if they negotiate or renew deals with Australian news media publishers to pay for hosting news content.

Section 891 could apply to such taxes if they were found by Trump to be “discriminatory” against US companies. What “discriminatory” means is not clear.

Its been suggested that foreign citizens or companies could be protected from Section 891 by their country’s tax treaty with the US, under the standard approach that a later treaty prevails over an older code section. But Australia’s tax treaty with the US took effect in 1983, before the most recent re-enactment of Section 891 in the US tax code.

Miranda Stewart receives funding from the Australian Research Council. Miranda is on the Permanent Scientific Committee of the International Fiscal Association.

Source: View source