Introduction

In this post, we outline how we transformed the way we serve data for our machine learning (ML) models and why we chose Amazon Aurora Postgres as the storage layer for our new feature store. At Grab, we have always been at the forefront of leveraging technology to enhance our services and provide the best possible experience for our platform users. This journey has led us to transition from a traditional approach to a more sophisticated and efficient ML feature store.

Over the years, ML at Grab has progressed from being used for specific, tactical purposes to being utilised to create long-term business value. As the complexity of our systems and ML models increased, requiring richer amounts of data over time, our platforms faced new challenges in managing more complex features such as a large number of feature keys (high-cardinality) and high-dimensional data or vectors. This evolution necessitated a shift in our data processing and management strategy. We needed a system to store and manage these complex features efficiently. In November 2023, this brought us back to the drawing board to evolve from Amphawa, our initial feature store.

We landed on the concept of feature tables: a set of data lake tables for ML features that are automatically and atomically ingested into our serving layer. While this concept is not new to the industry, as other platforms like Databricks and Tecton have evolved towards it, our approach is focused on atomicity and reproducibility. The rationale is that ensuring consistency and reliability during the serving lifecycle has become more critical, which has made it more challenging to manage within the model serving layer itself.

From feature store to data serving

A feature store is a repository that stores, serves, and manages ML features. It provides a unified platform where data scientists can access and share features, reducing redundancy and ensuring consistency across different models.

Our feature data is a key-value dataset. The key identifies a specific entity, such as a consumer ID, which is a known value in the incoming request. A composite key is supported by concatenating two or more entity identifiers. For example, (key = consumer_id + restaurant_id). The value is a binary that encodes the feature value and its type. Whenever a new value for a given entity needs to be updated, we write a new key-value pair for that entity.

New functional requirements

As our users designed and deployed increasingly complex ML solutions, new essential functional requirements were requested by our users:

- Ability to retrieve the features given in the composite keys (contextual retrieval): The ML models in an upstream service might need to fetch all matching entities to form complete contextual information in order to make the recommendation. We build that context inside our ML orchestration layer before calling the model. This was previously not possible due to the design of composite keys in our initial approach.

- Ability to update not just one entity atomically, but all the entities in a collection (atomic updates): This requirement concerns reducing the complexity of operations, such as rolling out new models and switching between versions of feature data. In Amphawa, newly ingested data is visible to consumer systems immediately after it’s written. As changes to the data may be ingested over a long period of time, users are responsible for ensuring the models or services don’t break while the new and old data coexist during ingestion, especially during potentially breaking changes to data. This complexity translates into quite complex code, which is hard to refactor over time. With the new approach, all feature changes will only become visible through atomic updates once the entire operation finishes successfully. This eases users’ pain of maintaining compatibility across versions.

- Isolation of reading and writing capacity: The noisy-neighbor effect is one of the significant issues in our centralised feature store. Different readers could compete for read capacity. For some storage systems, write traffic could consume I/O capacity and affect reading latency. While reading capacity can be adjusted by scaling the storage, the competition between reading and writing capacity is highly dependent on the choice of storage. Hence, from the beginning, one of the top requirements of our second-generation feature store design was isolating reads from writes.

Feature table

To meet the functional requirements, we landed on the concept of a “feature table,” where users define and manage the schema and data on a per-table basis. Feature consumers can customise their tables based on their needs. Working with a table format directly makes it easier for data scientists to work with complex tabular data that needs to be retrieved in different ways depending on the context of the request. Moreover, it’s more manageable for us, on the platform side, because it’s closer to the actual format in the storage layer.

| Amphawa (feature-centric) | New design (feature-table centric) |

|---|---|

| A user defines individual features and their types. Grouping into the table is storage layer is implicit. | A user defines their tables with compatibility with data-lake tools such as Spark. |

| The only index is on the data key. | A user defines their own indexes for their tables, based on their access pattern. |

Table 1: Comparison between Amphawa and the new feature table.

Our feature tables are not just a storage solution but a critical component of our ML infrastructure. They enable us to simplify our feature management, efficiently handle the model lifecycle, and enhance our ML models’ performance. This has allowed us to provide a better experience for our platform users and dramatically improve the quality of our ML models based on our A/B testing results.

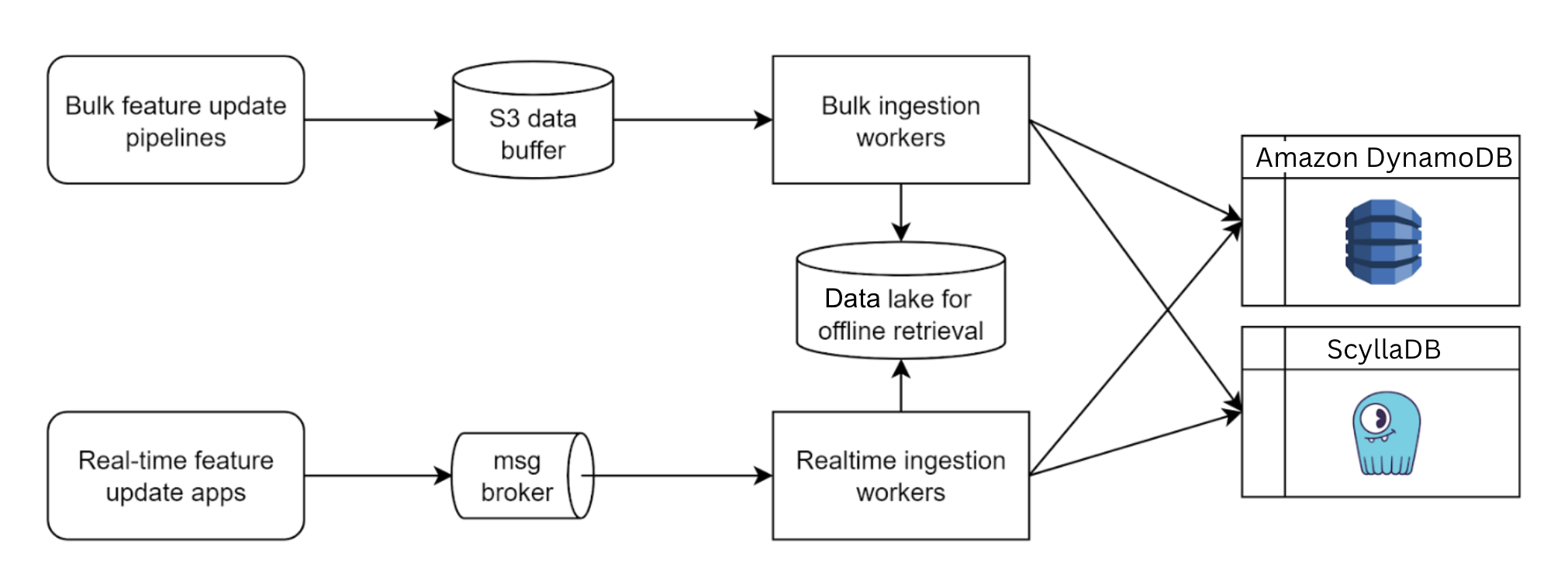

The data serving’s ingestion workflow

We designed an ingestion framework to address the atomicity requirements from the ground up.

The data ingestion process in Amphawa was meticulously crafted to ensure efficiency and reduce the pressure on the key-value store. Conversely, our priority has shifted to atomicity (all or nothing) to serve our feature tables and simplify version compatibility.

- Landing feature table in the data lake: Data scientists use SQL or Python on Spark to build ML pipelines that output data lake tables. These tables and metadata for version control are stored as Parquet objects in Amazon S3.

- Register collection summary: A “collection summary” consists of a group of feature tables to be served and other related metadata regarding customised individual tables. In this step, our registry will validate the table’s schema and ensure the customisations are defined correctly.

- Deploy collection summary: Data scientists send another request to our registry to deploy a collection summary.

- Pre-ingestion validation: The schema is validated to ensure compatibility with the target online ML models. This process ensures consistency and compatibility across feature updates.

- Ingestion: The ingestion mechanism is a classic reverse ETL where the data from S3 is loaded into our Aurora Postgres tables.

- Post-ingestion warm-up: To avoid cold-start latency spikes, shadow reading duplicates a part of the ongoing reading queries to the new tables for a period before the final switch.

One of the core propositions of feature tables is to offer a simplified interface for writing. Compared to writing directly to a database or providing SDKs for different processing frameworks, we provide a single, common interface for writing, independent of the actual choice of database. This allows us to evolve or even integrate feature tables with other data stores without requiring our users to modify their pipelines. We can decide how the data is represented in the database at a specific isolation level while guaranteeing total transparency for writes and reducing the complexity of read operations.

However, if a producer has access to S3 and can write in a columnar format, they can always write feature tables. This also means they can access samples from the data lake and use other tools for data validation, as well as tools for data discovery.

Do take note that a feature table can only be used for data that can be represented in tabular format and requires a minimum of one index to be present in the data. In this initial phase, we support the following data types:

- Atomic types (int, long, boolean, string, float, double)

- List of atomic types (List[atomic])

- List of list of atomic types (2d array)

- Dictionary with strict types of keys and values

Leveraging AWS Aurora for Postgres to meet our non-functional requirements

In our quest to optimise our ML infrastructure, we strategically decided to use Amazon Web Services (AWS) Aurora for PostgreSQL to meet our non-functional requirements. Aurora’s unique features and capabilities, which aligned perfectly with our operational needs, drove this decision.

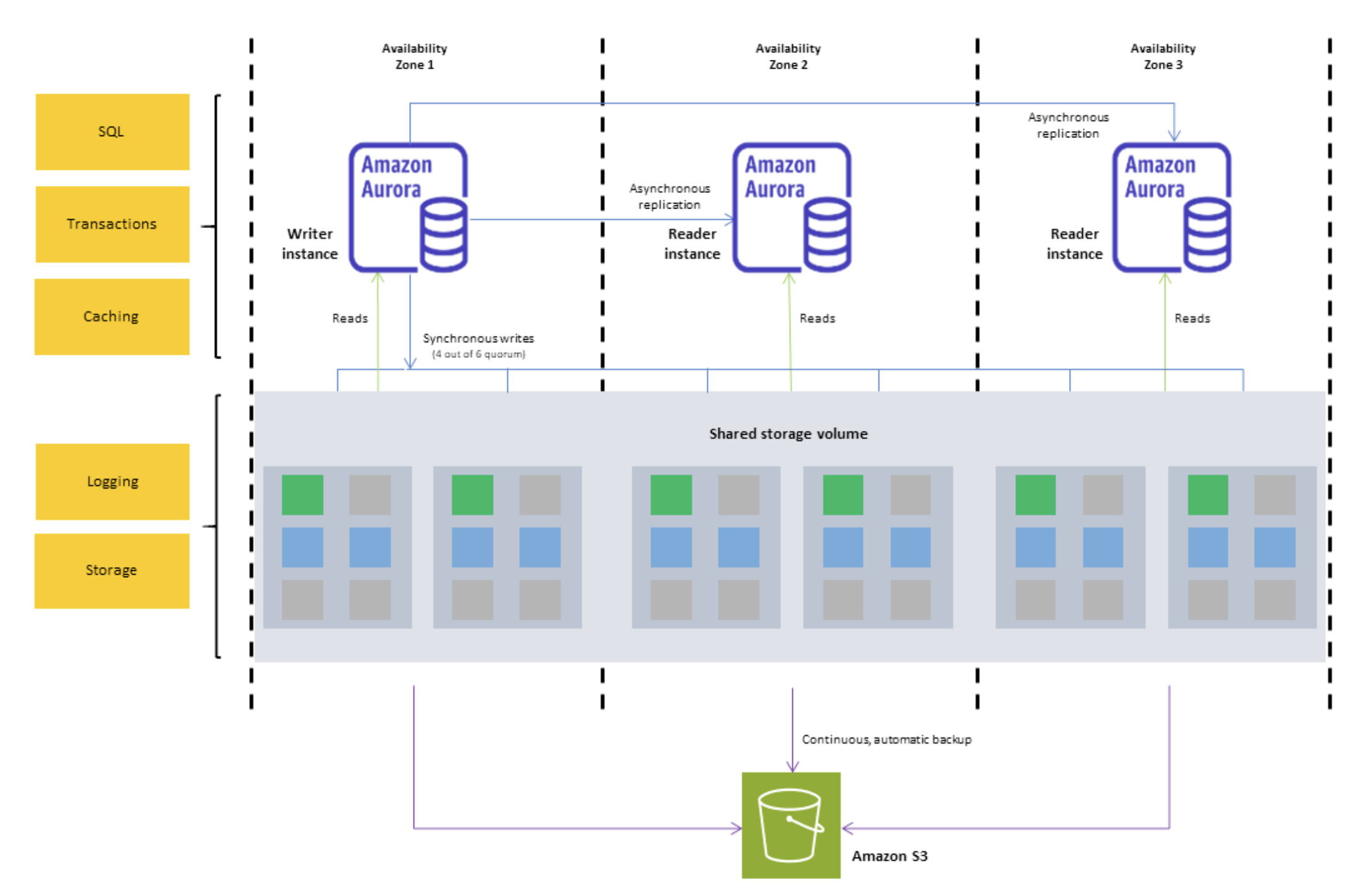

AWS Aurora is a fully managed relational database service that combines the speed and reliability of high-end commercial databases with the simplicity and cost-effectiveness of open-source databases. A key differentiator is Aurora’s distributed storage architecture.

Architecture breakdown

The cluster volume consists of copies of the data across three “Availability Zones” in a single AWS Region. Since each database instance in the cluster reads from the distributed storage, this allows for minimal replication lag and ease of scaling out read replicas to meet performance requirements as traffic patterns change.

The separation between readers and writers also allows us to scale each independently. This is a crucial feature as our traffic is predominantly read-heavy. Most of our data-writes occur once a day. Using a serverless instance class with the writer node being scaled down during idle time significantly reduces our overall operational costs.

The independent scaling of reader and writer nodes allows us to maintain high performance and availability of our feature store. During peak read times, we can scale out the reader nodes to handle the increased load, ensuring that our ML models have uninterrupted access to the features they need. Conversely, during periods of heavy data ingestion, we can scale up the writer nodes to ensure efficient data storage.

To facilitate the seamless scaling up and down of the writer node, Aurora also allows a cluster to have a mixture of Serverless and Provisioned nodes. The key difference between the two is that with Serverless, the Aurora service manages the capacity of a single node and adjusts accordingly as the load increases and decreases. In our context, we’re using Serverless for our writer node to quickly scale up when heavy data ingestion starts and scale down automatically once the ingestion is done. We then use Provisioned nodes for the reader nodes since read traffic is more consistent.

In addition to cost and performance benefits, AWS Aurora simplifies our database management tasks. As a fully managed service, Aurora takes care of time-consuming database administration tasks such as hardware provisioning, software patching, setup, configuration, or backups, allowing our team to focus on optimising our ML models.

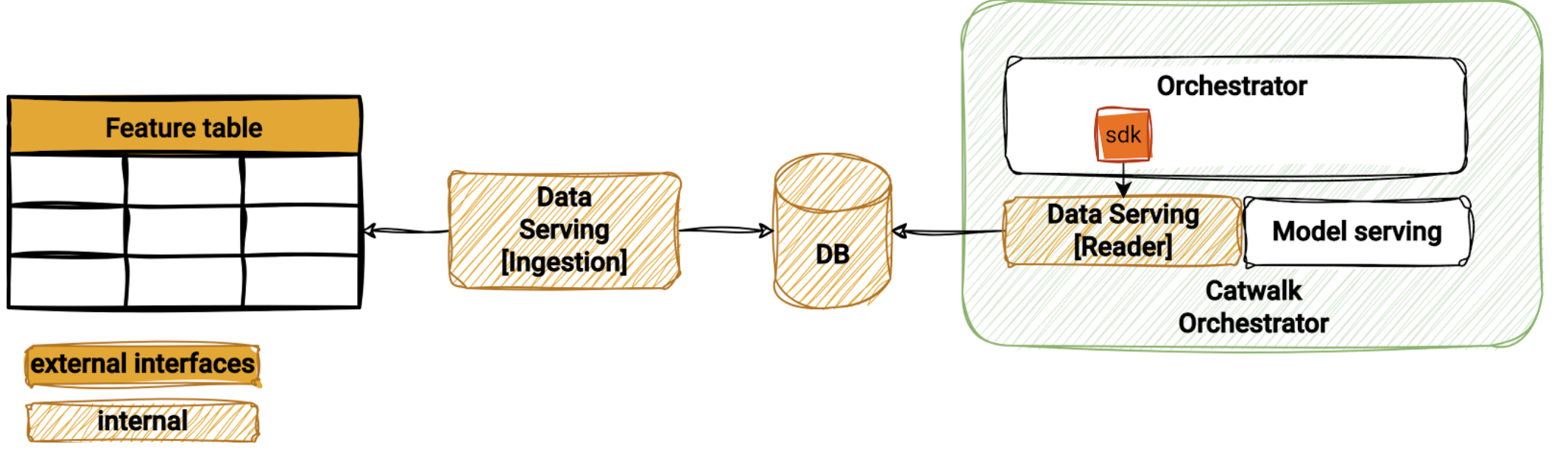

Accessing the data through our SDK

With the goal of providing a high-performing and highly available data serving SDK design, we’ve moved on from the centralised API design of Amphawa to a decentralised access architecture in Data Serving. Each data serving deployment is a self-contained system with a cluster and feature catalogue stored within the cluster as additional metadata tables. This minimises dependency, which improves the availability of the system.

The data serving SDK is designed to be a thin wrapper around the database driver to optimise performance. The SDK contains only a set of utility functions that load user configuration from the Catwalk platform and a query builder to translate user queries to SQL. No additional data validation is performed in the query code path, as all validation is done during feature table generation and ingestion. Therefore, the database handles most of the heavy lifting.

Decentralised deployments: A strategic shift in our infrastructure

We also investigated the difference between centralised and decentralised deployments. We have been exploring these options in the context of our ML feature store, specifically with our Amphawa service and Catwalk orchestrators.

Our original feature store was deployed as a standalone service where different model-serving applications can connect to it. On the other hand, a decentralised deployment is integrated within a model-serving orchestrator, and a specific orchestrator is bound to a set of pods.

After extensive discussions and evaluations, we concluded that a decentralised deployment for data serving would better align with our operational needs and objectives. Below is the list of factors we compared that led us to this decision:

- Version control: Centralised deployments simplify version control but risk accumulating technical debt due to backward compatibility requirements. Decentralised deployments, while needing robust tracking, offer more flexibility.

- Deployment strategies: Decentralised deployments enabled seamless use of Blue-green and Rolling Deployment strategies. They allow multiple versions to coexist and easy rollbacks, reducing client mismatch issues.

- Noisy neighbour problem: Centralised deployments struggle with the noisy neighbour issue, which requires complex rate limiting. Decentralised setups mitigate this problem by isolating services.

- Caching efficiency: Centralised deployments often suffer low cache hits, whereas decentralised deployments improve caching efficiency by better fitting data into the cache.

Conclusion

In conclusion, leveraging AWS Aurora for Postgres has enabled us to create a robust, scalable, and cost-effective feature store that supports our complex ML infrastructure. This is a testament to our commitment to using cutting-edge technology to enhance our services and provide the best possible experience for our users. Our shift towards decentralised deployments represents our dedication to optimising our infrastructure to support our ML models effectively. By aligning our deployment strategy with our operational needs, we aim to enhance the performance of our services and provide the best possible experience for our users.

Join us

Grab is a leading superapp in Southeast Asia, operating across the deliveries, mobility and digital financial services sectors. Serving over 800 cities in eight Southeast Asian countries, Grab enables millions of people everyday to order food or groceries, send packages, hail a ride or taxi, pay for online purchases or access services such as lending and insurance, all through a single app. Grab was founded in 2012 with the mission to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. Grab strives to serve a triple bottom line – we aim to simultaneously deliver financial performance for our shareholders and have a positive social impact, which includes economic empowerment for millions of people in the region, while mitigating our environmental footprint.

Powered by technology and driven by heart, our mission is to drive Southeast Asia forward by creating economic empowerment for everyone. If this mission speaks to you, join our team today!