Table of Contents

It’s interesting to know how the JVM runs bytecode instructions… But do you know what is going on when an exception is thrown? How does the JVM handle the delegation of control? What does it look like in the bytecode?

Let me quickly show you!

Example

Here’s a simple bit of Java code that includes all the important actors in the exception-throwing game (try-catch-finally):

int a = 0;

try {

if (a == 0) { // to make it less boring, let's have some branching logic

throw new Exception("Exception message!");

}

} catch (Exception e) {

doSomethingOnException();

} finally {

doSomethingFinally();

}

Exception table

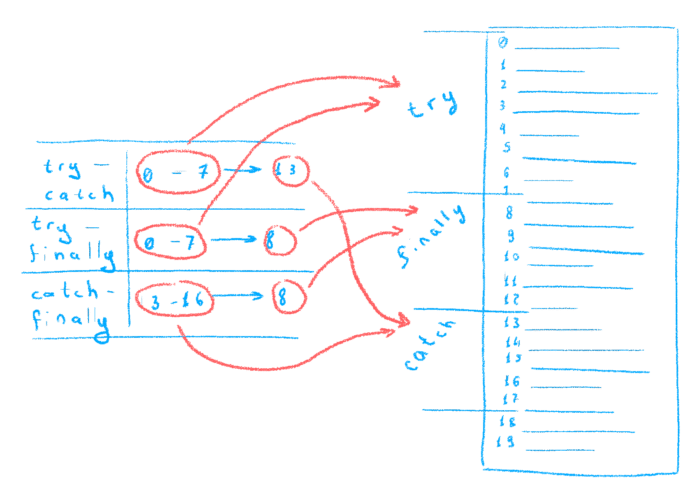

The resulting bytecode includes an interesting section in the Code attribute called the Exception table. Each method can have its own exception table, and it’s only present when relevant. If there is no exception-handling logic in the method, it won’t have an exception table.

This is how the exception table looks like for our example:

Exception table:

from to target type

2 16 22 Class java/lang/Exception

2 16 32 any

22 26 32 any

The numbers point to the addresses of the bytecode instructions. Each line in this table shows a range of bytecode instructions (from and to) that is guarded by an exception handler. The handler itself is also just a set of bytecode instructions, and the target column points to the address where the handling code starts. type simply means the type of exception that can be handled by the specified handler.

Bytecode instructions

To see what exactly these addresses are pointing to, let’s take a look also at the set of method’s bytecode instructions (explanation below):

0: iconst_0

1: istore_0

2: iload_0

3: ifne 16

6: new #12 // class java/lang/Exception

9: dup

10: ldc #14 // String Exception message!

12: invokespecial #16 // Method java/lang/Exception."<init>":(Ljava/lang/String;)V

15: athrow

16: invokestatic #19 // Method doSomethingFinally:()V

19: goto 38

22: astore_1

23: invokestatic #22 // Method doSomethingOnException:()V

26: invokestatic #19 // Method doSomethingFinally:()V

29: goto 38

32: astore_2

33: invokestatic #19 // Method doSomethingFinally:()V

36: aload_2

37: athrow

38: return

Let me walk you through.

Instructions 0 - 2 are responsible for creating a variable int a = 0;.

Then, we have an ifne, which is a conditional jump, with 16 being an address where to jump. If a is not equal to 0, we jump to instruction at the address 16. There, we find the contents of our finally block, followed by a goto instruction pointing to the end of the method.

If the condition is false, we continue onto the next instruction. Instructions 6 - 12 handle the creation of an Exception instance. Note that the reference to this instance is duplicated, so by the end of this set of instructions, it appears twice on the operand stack.

The instruction at the address 15, athrow, is responsible for actually throwing the exception! It “eats” one of the references to our Exception instance from the operand stack, which tells it which exception to throw. In fact, it clears the whole stack, leaving only a single reference to the exception on top.

When the JVM encounters athrow instruction, it checks the method’s exception table in order to find the appropriate location to continue execution.

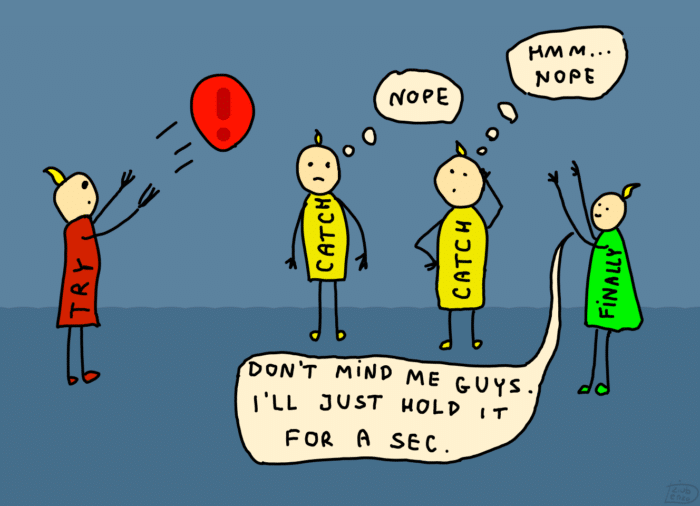

Try-catch-finally flow

Let’s take another look at the exception table now that we have more context.

Exception table:

from to target type

2 16 22 Class java/lang/Exception

2 16 32 any

22 26 32 any

We encountered athrow at address 15. This address is covered by the first two lines of the table, as it falls within the range [2, 16).

Why two handlers? One is a catch block (target points to 22, where the catch logic starts), and the other is a finally block (target 32 is pointing to the finally logic). The third line of this table covers the range of instructions containing our catch logic, and the target points to the finally block. This means that if anything happens during the execution of a catch block, we still want to end up in the finally block.

When we are in a catch block (address 22), something from the operand stack is stored into a variable. We had an extra reference to the Exception instance on our stack, remember? Here, the astore instruction saves it as a variable. Internally, a variable doesn’t have a name, but logically, this is our variable e, which we can use in the catch block to log it or do anything else with it.

Less nice flow

This was a “nice” flow. The JVM looked into the exception table and found a handler that knew what to do with the Exception. If there was only a finally handler, that wouldn’t have been enough.

How does the JVM know if it’s a catch or a finally handler? We can see that a type column for finally handler contains any type, meaning that it should be executed in any case, regardless of whether an exception is thrown. If an actual type is specified instead, it’s a catch handler. The type that the JVM is looking for is an exact type of the exception or its supertype.

What if there is no appropriate handler? In that case, the JVM stops execution of the current frame and returns to the previous frame (to the method that called the current method). It continues going to the previous frames until it finds an appropriate catch handler for the given exception. Note that if it finds a finally handler which is applicable by address range, it will execute it on the way too. If there is no catch handler all the way through the stack, the JVM terminates the thread and prints out the stacktrace.

Summarized flow

The try-catch-finally mechanism can be summarized as follows:

- The

athrowinstruction tells the JVM that an exception is thrown. Which exception? The one that’s on top of the operand stack. - When this happens, the JVM checks the exception table of this particular method. Given the address of

athrowinstruction, it can find the address of appropriate handler(s). - If a

catchhandler is found (the handler that has a correct exception type in thetypecolumn), the reference to the exception is saved from the stack as a variable. Then, thecatchlogic is executed. - If a

finallyhandler is found, it’s executed. - If no appropriate

catchhandler is found, the JVM terminates execution of the current frame and looks for a handler in the previous frame. - The JVM goes through all frames until it finds a

catchhandler, executing anyfinallyhandlers that it finds along the way.

If no handler is found, the program’s execution is terminated.

That’s it for now! See you in the next nerding session 🤓

The post How JVM handles exceptions appeared first on foojay.

Source: View source