How Art Lost Its Way

William Deresiewicz | Persuasion | 6th January 2025 | U

An unserious culture lacks the ability to sustain high art.

Now I’ll never have a chance to impress Arlene Croce.

Croce, who died last month at 90, was the dean of American dance critics during the heyday of American dance. I started my writing career as a dance critic, too, and for many years that’s all I ever dreamed of being as a writer. My first sixty-plus published articles were dance reviews, and their intended audience consisted, in its entirety, of Arlene Croce. She was the lodestar, the queen, the presence around which the field arranged itself. I’ve wanted few things more in life—wanted it with the ardor of youth and the thirst for praise of the apprentice writer—than to win her approval.

I never did. In fact, I’ve no idea if she ever saw a word I wrote. But her death brought me back to that time. In retrospect, it was the waning days of the golden age of an American art form whose achievements bear comparison to those of Florentine painting or Viennese music. Not many remember this now, for dance leaves little to posterity. It cannot be hung on a wall, recreated from a score, or discovered in a book—cannot be experienced outside the moment of performance and the physical presence of the performers. The camera can record it but it cannot capture it, still less preserve it. It is here one moment, gone the next. You have to be there, which means you had to be there, and by there I mean the southern half of Manhattan, which is where the phenomenon largely took place: in the concert halls of Midtown, the performance spaces of the East Village, the lofts of Soho and Tribeca, the little theaters of West 19th Street.

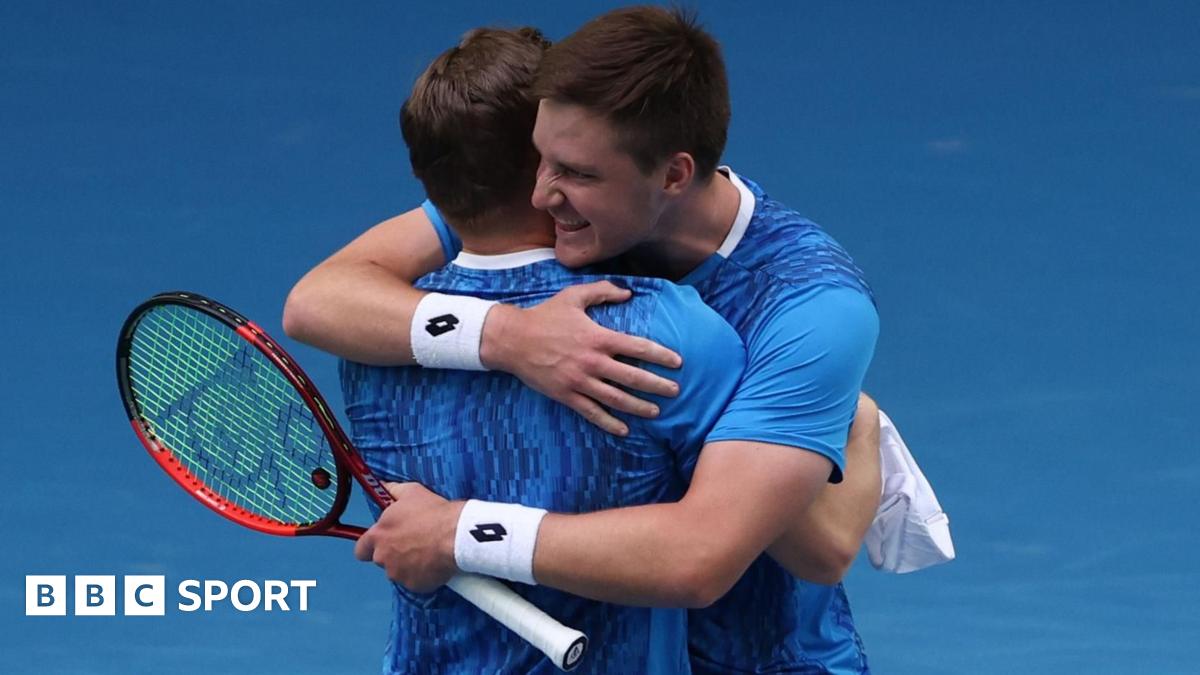

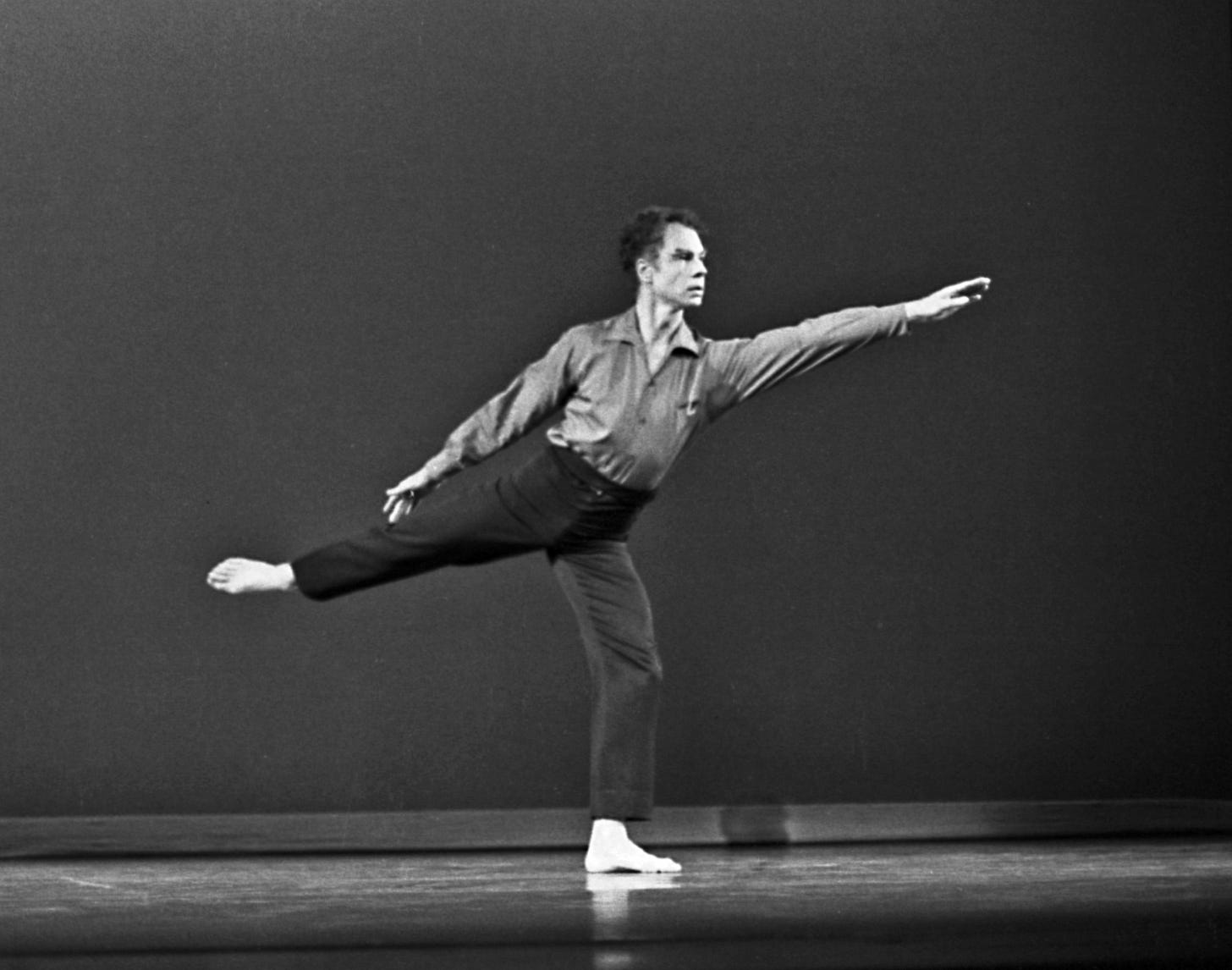

If you had you would have seen the works of George Balanchine—crystalline in their classical purity, daring and sleek in their modernist scale and velocity—performed by a New York City Ballet, the company he founded, that still bore his imprint. Of Merce Cunningham, dance’s great aesthetic revolutionary (it is said that if Balanchine freed dance from story and tied it to music, Cunningham freed it from both)—beautiful as a hart, enigmatic as an Easter Island statue, self-sufficient as a mathematical equation. Of Paul Taylor at the height of his invention, his dances buoyant and joyous and generous, the image in muscle and movement of a happy human world. Of Mark Morris, in the first flush of his genius, who showed up in the early ‘80s (it was Croce whose review in The New Yorker put him on the map) to reinvent the art all over again (“dance language as we have known it—old academic or anti-academic usage—falls from [his] bod[y] like rags”).

You would have seen the stalwarts of postmodern dance (Trisha Brown, David Gordon, Lucinda Childs, et al.), an experimental movement that had started in the early ’60s and had nothing in common with postmodernism in the later sense but a great deal with performance art. You would have seen an ever-replenishing cadre of young choreographers (Ralph Lemon, Susan Marshall, Neil Greenberg, etc., etc.) who staged their works in downtown studios, old churches, and repurposed public schools. You would have seen the dancers: young people who’d arrived from Missouri or Montana, or Switzerland or Argentina, to live in fifth-floor walk-ups, work in restaurants, and show us what the ancients meant by gods.

The great age of American dance was also, inevitably, the great age of American dance writing. It was Edwin Denby, the leading critic of the previous generation, who remarked that art is an attempt to prolong our experience of pleasure. If so, then criticism is an attempt to prolong our experience of art. In dance’s case, this is a devilishly tricky task: because you have to translate movement into words, the most corporeal art into the most cerebral medium, but even more because of dance’s very evanescence. By the time you get to your desk—by the time you get to the lobby—the thing is gone, and all that’s left is quickly fading memories, or as Croce put it in the title of her first collection, “afterimages.”

Nobody did it better than she—her prose was magisterial, her knowledge comprehensive, her eye and ear (for dancing is also a musical art) impeccable—but a lot of people were doing it really well. I took a class in dance criticism in 1987 (it’s the way I got into the field, into writing, into the rest of my life, really). The teacher was Tobi Tobias, then the dance columnist at New York Magazine. Week by week, she introduced us to the writing of the rest of what turned out to be a matriarchy: after Croce, Marcia Siegel, who wrote for The Hudson Review; Deborah Jowitt, possessed of an eidetic memory and loose, conversational style, who produced a full page weekly for The Village Voice; Mindy Aloff, who wrote for The Nation; Joan Acocella, with her sweet, clear prose, who eventually succeeded Croce at The New Yorker.

Don’t miss what’s most remarkable in all of this. New York Magazine had a dance columnist. The Nation had a dance columnist. The Village Voice had a dance columnist (The Village Voice existed, as more than just another website). The New Yorker still has a dance columnist (it is Jennifer Homans at present), but she has published all of 13 reviews in the six years she has occupied the position. For most of her tenure at the magazine, which ran from 1973 to 1996, Croce wrote at least that many every year. Like dance itself, dance criticism was a presence in the culture.

And not just dance criticism. The cultural environment I entered when I came of age in New York and began to tune into the arts was one defined, in part, by the vividness and variety of its critical voices: Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris on film, Robert Hughes on art, John Leonard and Elizabeth Hardwick on books, Michael Sorkin and Ada Louise Huxtable on architecture, Robert Christgau on rock, Stanley Crouch on jazz. The decline of arts criticism, since the arrival of the internet and the collapse of journalism’s business model, is by now a much-told story, but if it’s ever going to reverse itself, we need to understand why criticism mattered in the first place—what it did and how.

What all those very different figures had in common, aside from the excellence of their prose—and this is what distinguishes their criticism from most of what passes for cultural discourse today—is that their writing was grounded in a direct encounter with the work. They weren’t distracted by moralistic agendas, topical talking points, or biographical chitchat. They started with their own response and built out from there, seeking to grasp how it was that the work had incited it. Which also means that they trusted their own judgment. They weren’t looking over their shoulder; they couldn’t give a damn about the discourse. They didn’t write “takes,” which are not about the work but how you want the other kids to see you. They wrote to please themselves. They wrote to render justice to the art they loved.

Which meant their voices, like their opinions, could be distinctively their own. So much of criticism now seems written not just for the dinner party but by it. But they avoided cultured cant, campus jargon, critical clichés. They didn’t make internet-speak, or New Yorker–speak (the magazine was very different then). They wrote like individuals; they wrote like human beings; they wrote like members of the audience, fellow devotees, only much, much smarter than the rest of us.

Remember: Persuasion is now the home of American Purpose, Francis Fukuyama’s blog, and the Bookstack podcast! Opt in using your account settings to receive all of this great content via email:

That is why the rest of us could trust them. One of the functions of serious criticism has always been to lead the audience to new and challenging work, work that shocks and confuses, that violates conventions and defiles decorums. Criticism, not coincidentally, arose with Romanticism, at the dawn of modernity and in the age of revolutions, when, for the first time, artists sought not to work within traditions but to break them and to break with them. The avant-garde depended on the audience possessing a vanguard as well, and that is what the finest critics were. They were the first to get it and the best at explaining it.

So Hazlitt championed Wordsworth; Ruskin, Turner; Lewis Mumford, Herman Melville; Edmund Wilson, the high modernism of Proust, Joyce, and others. In dance, Croce championed Morris; Denby, Balanchine; John Martin, in the 1930s, Martha Graham. So grateful for his early support was Toni Morrison to John Leonard that she invited him to accompany her to Stockholm when she received the Nobel Prize. And so forth. “Critics with dazzling track records,” the great Dave Hickey wrote, “were willing to put their reputations on the line, take chances, and make public bets on the value and longevity of problematic artworks.”

But the audience needs to cooperate. It needs to want to go beyond itself. And that it did, in the decades after World War II, in the midst of the “culture boom,” with the expanding and aspiring middle class. Sure, there was a lot of bullshit there—a lot of status-mongering, a lot of pretension, a lot of middlebrow “art appreciation.” But there was also a lot that was real: a real desire for expanded consciousness, for spiritual depth, for a world made new by art, especially among the young and especially in New York.

And that is what I don’t see anymore. I have no doubt that there is still strenuous art being made, and that it is being received with attention and written about with intelligence. But almost all of that activity, as far as I can tell, is happening in coteries, in social niches and geographic pockets: poets doing readings for other poets, art that isn’t seen outside of Bushwick, critics writing for specialized websites or personal Substacks. What’s gone missing, in a society that long ago excused itself from seriousness, is a broader sense that art is urgent business, that your life, in some sense, depends on it. With that goes the mass audience. With that goes not only the possibility of meaningful criticism, but also its point. No one needs help understanding White Lotus, or Amanda Gorman, or Sally Rooney. For such creations, we can make do with “cultural criticism”—moralistic agendas, topical talking points, biographical chitchat—which is not arts criticism but a simulacrum thereof, and which any self-respecting gender studies major can produce.

Two further losses should be tallied here. The first is that other mediating institution, college. That is where you were supposed to begin your apprenticeship to the idea that there are traditions of thought and expression that it is your obligation to make yourself worthy of. There used to be a teacher at Columbia, an instructor in the great books program, who was famous for including in his final a question that ran, more or less, “Which of the books that we read this year did you find the least interesting, and what failing in you does that reveal?” Now, of course, a work like Moby-Dick is brought into the classroom not to be learned from but hectored. Or would be, if it were even still taught, which it isn’t, because students won’t read it, because they can’t.

The other loss is the city—I mean New York City, but also a kind of urban life more broadly. The New York audience in the decades after the war was aware of itself not just as individuals but as a body. The duty to be receptive, to be sophisticated, to self-transcend—and the grand adventure of it, too—was felt to be a collective one. You saw each other in the theaters, the galleries, the music clubs, the independent bookstores, saw each other in each other and knew that you were all engaged in something bigger together. That so many of the critics whom I mentioned earlier appeared in the Voice—not just Jowitt but Sarris, Sorkin, Christgau, and Crouch, plus many others whom I might have named—was quite to the point. The Voice, as people used to say and everybody understood, was the place where New Yorkers learned to be New Yorkers. And that was part of what you learned.

Deep Reading Will Save Your SoulWilliam Deresiewicz·May 29, 2024Read full story

That kind of urban existence, of collective urban consciousness, is largely gone—in New York, but also in San Francisco, in Austin, from everything I hear, in Portland, Oregon. Gentrification is a cause, the arrival of the tech bros and the oligarchs and pricing out of artists and bohemians, but the major cause is what the internet has done to daily life. I have friends who lived near Times Square in the mid-2000’s in a studio the size of a suburban bedroom. It was fine, one of them told me, because he spent the whole day in the city anyway, only coming home at night to sleep. Now people stay in, with their laptops and apps, especially people with the kind of disposable income that the arts rely on. The very fabric of the city is being shredded to accommodate the shift, as all-inclusive new developments—with gyms, coffee shops, roof deck socializing—offer lifestyles that are fully self-contained. Your condo, like your consciousness, exists as a node in a network, not a point in contiguous space, and you never need to know that you live in a city at all. This is the death of the urban idea.

All of which—the decay of ambitious criticism and everything that’s caused and comes from it—undoubtedly helps explain the most striking fact about the arts in America over the last few decades: their stagnation. From roughly 1945 to 1990, this country fostered a dazzling succession of creative developments: Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Conceptualism; bebop, folk rock, hip-hop, and punk; neoclassical ballet, postmodern dance, and performance art; Beat poetry and the New York School; the Jewish novel and the African-American novel; the Black Arts Movement; the New Hollywood; Off-Off-Broadway; and the New Journalism. Since then, and especially over the last 20 years, it feels like we’ve been trudging in a circle.

Nothing’s coming back, because nothing does come back. What Merce said of dance—that it runs like water through your fingers—is true of everything. I hear that, with the possibilities that platforms like Substack provide, plans are underway to revive the craft of criticism as a cultural force. (My very editor for this piece, Sam Kahn, is about to launch, with a couple of fellow writers, a new literary review.) I wish the individuals involved good luck, knowing only that if they’re going to succeed, they will have to find a way to do so under circumstances very different from the ones that enabled the last efflorescence.

William Deresiewicz is an essayist and critic. He is the author of five books including Excellent Sheep,

Source: View source