Abstract

The Integrity Data Platform (IDP) team decided to rewrite one of our heavy Queries Per Second (QPS) Golang microservices in Rust. It resulted in 70% infrastructure savings at a similar performance, but was not without its pitfalls. This article will elaborate on:

- How we picked what to rewrite in Rust.

- Approach taken to tackle the rewrite.

- The pitfalls and speed bumps along the way.

- Was it worthwhile?

Introduction

Grab is predominantly based on a microservice architecture, with the vast majority of microservices being hosted in a monorepo and written in Golang. It has served the company well so far, as the “simplicity” of Golang allows developers to ramp up and iterate quickly.

However, Rust has seen some gradual adoption across the company. Starting with a few minor CLIs, which then progressed to notable success with a Rust-based reverse proxy in Catwalk for model serving. Additionally, a growing community of Rust enthusiasts within the organisation has expressed interest in advocating for and expanding the adoption of Rust more proactively.

After achieving success with several projects on the ML platform and addressing concerns about Rust’s ability to handle traffic at scale, the next logical step was to assess the Return on Investment (ROI) of rewriting a Golang microservice in Rust.

Background

Rust has the reputation of being highly efficient yet poses a steep learning curve. Rust is often touted to perform close to C, doing away with garbage collection while remaining memory safe through strict compile checks and the borrow checker. It is loved by developers for having rich features like being multi-paradigm (supporting both functional and OOP style), having a rich type system, and doing away with nil pointers and errors.

However, regardless of how well regarded a certain language is in the industry, rewrites of any system should always be considered very carefully. When it comes to “legacy software”, there is a prevalent assumption that rewriting legacy software is a solution to eliminate technical debt and phase out legacy systems. The reality is often more nuanced.

Legacy code occurs when the developers who originally wrote the code are no longer working on the project. There are often business logic and edge-cases baked into complex legacy codebases of which the context has been lost over time. In practice, rewrites frequently take longer than anticipated and tend to reintroduce bugs and edge cases that must be identified and resolved all over again.

Rewriting vs refactoring has been written at length across the internet, you can read more about it here.

The trade-offs of rewriting need to be properly weighed and balanced. It must take into consideration:

- How much engineering bandwidth goes into the rewrite?

- What is the complexity of the rewrite?

- What tangible benefits are brought about by the rewrite?

Rewriting a system solely for the purpose of “rewriting it in Rust” is not a strong enough business justification.

A legitimate concern was the steep learning curve of Rust, coupled with the risk of having only one team member proficient in the language, which would make its adoption unsustainable.

Therefore, we established a set of guidelines to follow when identifying a suitable system for a potential rewrite:

- The system must be “simple” enough in functionality. For example, it has one or two main functionalities that can be rewritten in a reasonable amount of time and have its complexity constrained.

- The system targeted should have large enough traffic such that cost savings brought about by adopting Rust is something tangible when balanced against the effort.

- The members of the team must be comfortable and willing to pick up the language and achieve a certain level of familiarity to make maintaining the service sustainable.

Finding the right service

The ideal service should have a sufficiently large infrastructure footprint to justify the potential cost savings, while also being straightforward in functionality to minimise time spent on handling edge cases and complex business logic.

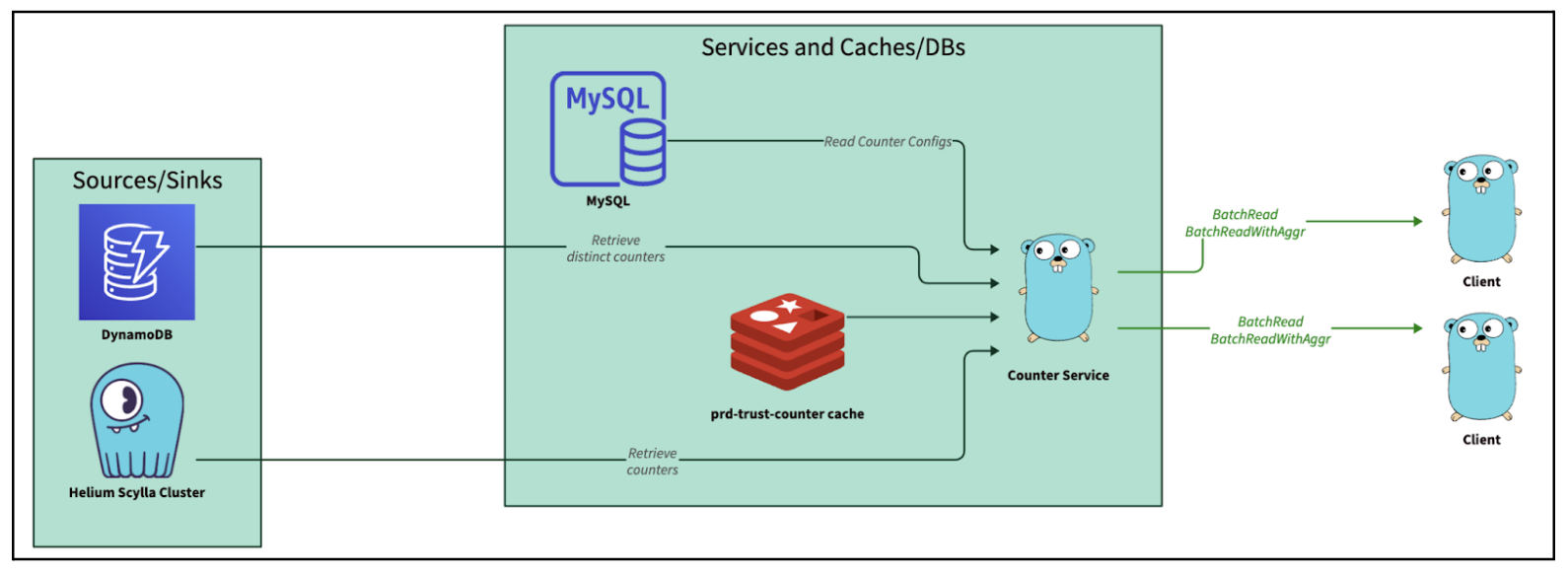

Looking across the stack of microservices in Integrity, Counter Service stands out. As its name implies, Counter Service is a service that “counts” and serves the counters for ML models and fraud rules. The original service has two primary functionalities:

- Consuming from streams, counting events and writing to Scylla.

- Exposing Google Remote Procedure Call (GRPC) endpoints to query from Scylla (and Redis) and return counts of events based on query keys. For example, BatchRead. BatchRead’s functionality of Counter Service serves up to tens of thousands of QPS at peak and is fairly constrained in functionality. Hence, it fulfilled our target criteria of being “simple” in functionality yet serving a large enough amount of traffic that justifies the ROI of a rewrite.

Rewrite approach

There are a few ways to approach a rewrite in another language. One popular way is to convert your code line by line. If the languages are close enough, it might even be possible to programmatically convert your code like C2Rust.

We decided not to use such an approach for our rewrite. The major reason is that idiomatic Golang was not necessarily idiomatic Rust. We wanted to approach this rewrite with a fresh perspective and treat this as a true rewrite.

We treated the application like a black box, with the interfaces well defined, like GRPC endpoints and contracts. Similar to a function, you could call the API and get a deterministic result, and we had the data that was stored in Scylla.

Based on how we understood the application to work based on its specs and contract, we chose to rewrite the application logic from scratch to meet the API contract and to get as close as identical outputs from the new black box.

OSS library support

We started out by mapping out the key external dependencies and checking how well they were supported in the Rust ecosystem and in open source.

Table 1: List of libraries and their star ratings

| Functionality | Library | Stars (as of Nov 24) |

|---|---|---|

| Datadog (Statsd Client) | https://github.com/56quarters/cadence | < 500 |

| Lightstep (OpenTelemetry) | https://github.com/56quarters/cadence | > 1000 |

| GRPC Server | https://github.com/hyperium/tonic | > 500 |

| Web Server | https://github.com/actix/actix-web | > 20,000 |

| Redis Client | https://github.com/aembke/fred.rs (Async Redis Library + Client pool) | > 5000 |

| Redis Client | https://github.com/redis-rs/redis-rs (“Official” redis client, initially picked but discarded) | > 3000 |

| Scylla Client | https://github.com/scylladb/scylla-rust-driver | ~500 |

| Kafka Client | https://github.com/kafka-rust/kafka-rust | >1000 |

All the functionality we need is available through libraries in the Rust ecosystem. However, we found that some libraries are not particularly “popular,” as indicated by their relatively low number of GitHub stars.

The practical concern with using less “popular” libraries is the risk of limited community support or potential abandonment over time. That said, if an “unpopular” library is officially maintained by the associated open-source project—for instance, the Scylla driver has only about 500 stars but is officially provided by the Scylla project—we would need to ensure confidence that it will continue to receive active support.

Out of the list of libraries above, the “unpopular” and unofficial libraries can be narrowed down to two libraries:

- Datadog - Cadence

- Redis - Fred

For Datadog, there is no “official” Datadog Rust client. Yet, we picked Cadence as the API looked intuitive and the features we needed were already supported.

In regards to Redis, after testing it, we discovered that the support was not up to par with our requirements. We then opted for a newer and less popular library, fred.rs that seemed to be actively being developed by the community.

Company specific internal libraries

With the vast majority of microservices being written in Golang, most internal libraries are also written in Golang. Opting to rewrite a service in Rust means we are not able to use these internal libraries.

Examples include:

- An internal configuration library that utilises Go Templates to template configurations for different environments (staging and production).

- The internal configuration library has its own wrappers and injectors to pull and render secrets.

To overcome this gap and re-use Go Templates and configuration language, we decided to write a simple wrapper and parser using the nom parser combinator to parse the templates and render the config.

Nom poses a steep learning curve. But once familiarised, it is flexible and performant enough to build an equivalent to the internal library. Parser combinators are an interesting subset of tooling that allows you to create some fairly elegant parsers.

Road bumps

The borrow checker

One of the most striking paradigm shifts for developers transitioning to Rust is adapting to the strict rules of the borrow checker, which enforces that variables cannot be reused multiple times unless explicitly cloned or borrowed.

Interestingly, the borrow checker was not the biggest hurdle for new developers. The key is to avoid introducing lifetimes too early in the development process, as this can lead to premature code optimisation.

In many cases, adding a few clones (and occasionally Arcs) can help new developers get up to speed and iterate more quickly during development. The resulting code is usually “fast” enough for initial purposes. After that, the code can be revisited to eliminate unnecessary clones for improved performance. An efficient approach to this can be taken by using Flamegraph to profile your code and identify memory allocation bottlenecks.

Async gotchas

When rewriting Golang logic in Rust, there are fundamental differences in how they treat concurrency and parallelism.

One of Golang’s most remarkable strengths is its ability to deliver high-performance concurrency while preserving simplicity.

There are two fundamental approaches to concurrency in programming languages, namely:

- Preemptive scheduling (stackful coroutines).

- Cooperative scheduling (stackless coroutines).

Preemptive vs cooperative scheduling is an in-depth topic with the gist of it being, Golang uses preemptive scheduling and each “Goroutine” has a stack that needs a runtime. The Golang scheduler has the power to “preempt” and “freeze” functions and switch to another stack like stackful coroutine. This is a gross oversimplification of the nuances. For more details, this is a good introduction to the topic.

Rust opts for cooperative scheduling whereby it has no runtime and each coroutine does not maintain a stack. Hence, it has no ability to “freeze” a function and swap context. This allows Rust to be more efficient in terms of memory and resources, as it maintains a state machine. However, the consequence is that this moves the complexity up the stack to the programming language itself. Similar to Javascript, functions are “coloured”, and the developer has to explicitly annotate their functions to be async or sync. Await points need to be explicitly called and control needs to be “yielded” (i.e. cooperative and stackless) so the Rust program knows when it is allowed to stop and swap between coroutines. To read more on this, refer to this and this article for the history of async Rust.

Needing to annotate a function is a classic complaint that is addressed in the article “What Colour is Your Function” that highlights developers’ responsibility to explicitly colour their function and consciously think about blocking vs non-blocking code.

Contrast this with Golang, where you simply need to add the go keyword without thinking about which code might block the execution and use channels to communicate across Goroutines. Golang allows the developer to achieve high performance without much cognitive overhead.

This is especially important for developers new to Rust. As the lack of experience in async and blocking code can be somewhat of a footgun. In the initial rewrite of Rust, we made an amateur mistake of using a synchronous Redis function to call the Redis cache. It resulted in the application performing poorly until we corrected it with the non-blocking asynchronous version using the Fred redis library.

Impact

Following the eventful process of rewriting the service from the ground up in Rust, the outcomes proved to be quite intriguing.

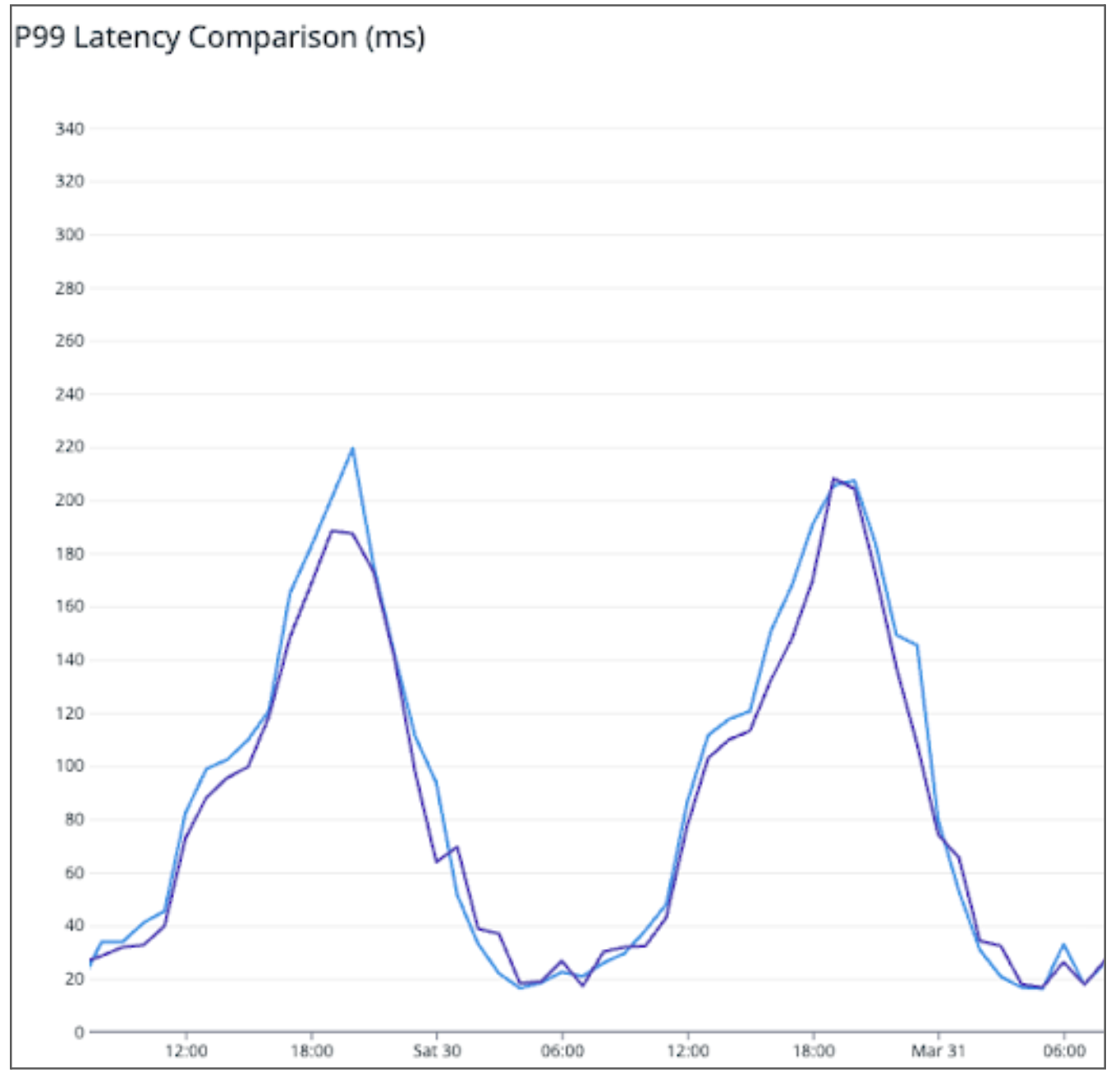

Shadowing traffic to both services as seen in Figure 2, the P99 latency is similar (or perhaps even slightly worse) in the Rust service compared to the original Golang one.

Normalising the QPS and resource consumption, we see from Table 2 that Rust consumes ~20% of the resources of the original Golang application, resulting in 5x savings in terms of resource consumption.

Table 2: Comparison of resource consumption between Rust and Golang service.

| Service | Indicative QPS | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Original Golang Service | 1,000 | 20 Cores |

| New Rust Service | 1,000 | 4.5 Cores |

Learnings and conclusion

The outcomes and insights from this rewrite have been eye-opening, debunking certain myths while also validating others.

Myth 1: Rust is blazingly fast! Faster than Golang!

Verdict: Disproved. Golang is “fast enough” for most use cases. It’s a mature language built with concurrency at its core, and it performs exceptionally well in its intended domain. While Rust can outperform Golang due to its higher performance ceiling and finer-grained control, rewriting a Golang service in Rust solely for performance improvements is unlikely to yield significant benefits.

Myth 2: Rust is more efficient than Golang

Verdict: True. Rewriting a Golang service in Rust will probably give you 50% savings in compute. Rust does fulfill its promise of being memory safe without garbage collection, allowing it to be one of the more efficient languages out there. This is in line with other discoveries in the market.

Myth 3: The learning curve of Rust is too high

Verdict: It depends. Pure synchronous Rust is fine. As long as you don’t overcomplicate the code and only clone what is needed, it is mostly true. The language is easy enough to pick up for most experienced developers. Even with cloning sprinkled in, the code is usually “fast enough”. The compiler is a good teacher, the compiler error m